JOAN KERR DANCE COMPANY and JUBA CONTEMPORARY DANCE THEATRE

Introduction

Early Horton-based companies in Philadelphia circa 1960-1980

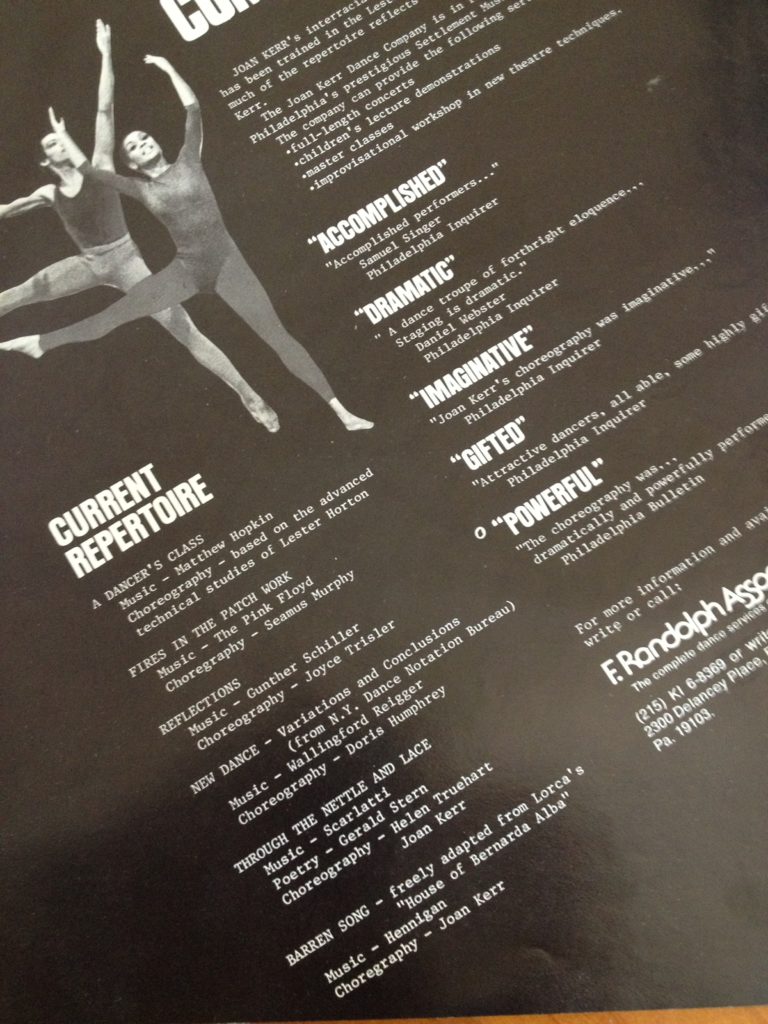

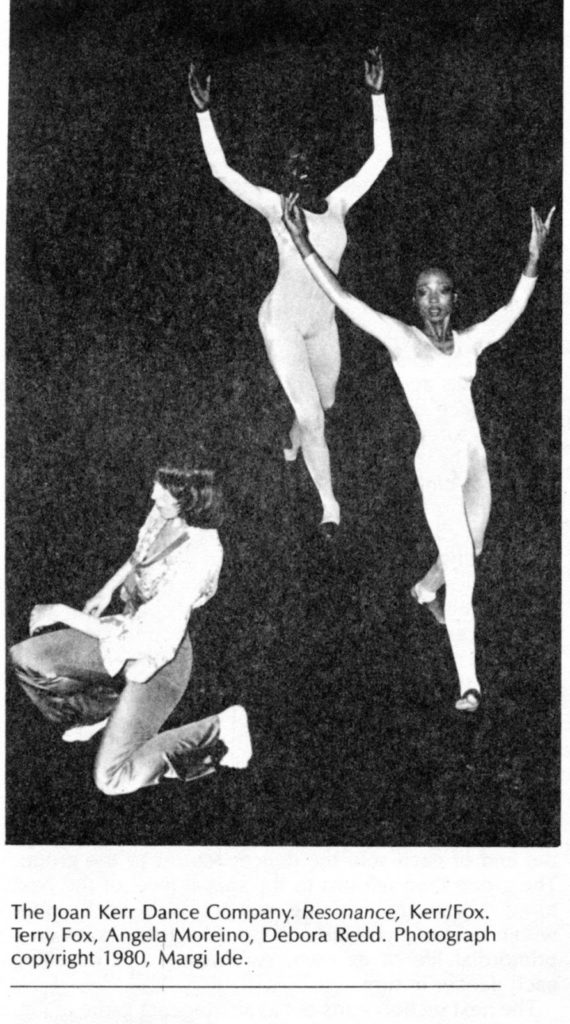

The provenance of Lester Horton’s dance technique in Philadelphia can be traced solely to Choreographer, Joan Kerr, who was a member of the Lester Horton Dance Theater in Los Angeles from 1952 to 1961. She returned to her hometown of Philadelphia in 1961 at the age of 27, where she taught for several years at the Philadelphia Dance Academy, before opening her own studio and founding the Joan Kerr Dance Company (JKDC).

In 1965 I was a first year student at Temple University. I took a dance elective with dancer and then PE Faculty, Katherine Pira. Temple’s modern dance group under her direction and sponsored by the University Women’s Athletic Association commissioned a work by Joan Kerr for their spring concert. I auditioned for Kerr and performed in the new work. It was a “choreodrama” based on a Greek theme. I vaguely recall the title being “The Libation Bearers,” but I could be entirely wrong, but that’s what we were about. I remember the costumes, a black draping Chiton with crisscrossing white cord, the extra braided hairpiece, and the opening moves, as we in the chorus moved onto stage, single file, the left hand cupped under the left breast, while the right arm snaked out, guiding our path. I am sure there was atonal music and plenty of Horton “hinges.”

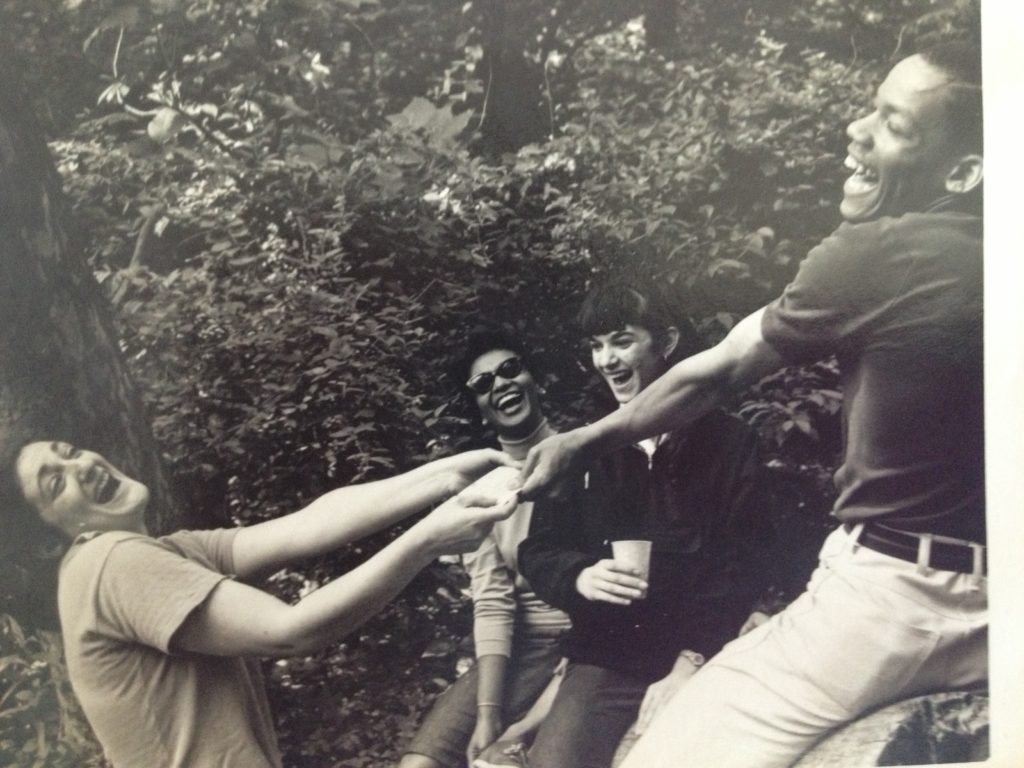

Half a century later I am considering the evolution of modern dance and some of those dance artists in the last half of the 20th century in to the millennium, as I am wanting to remember or at least mark this sector of artists in Philadelphia. It seems then essential to include Joan Kerr, as she established one of, if not the first, racially integrated dance companies here, modeled perhaps after Lester Horton, with whom she studied and performed. Her dissemination of the Horton Technique was acknowledged by many students and successors; including Judith Jamison, Faye Snow and Henry Roy among others. In addition, she fostered other local artists including Arthur Hall, whom she encouraged to investigate African heritage through dance, (The Arthur Hall Afro-American Dance Ensemble). He called her his mentor. His first concert was presented by Kerr at the YM-YWHA at Broad & Pine Streets in the 1960’s.

This small collection of oral histories and digital materials, is a start in recognizing Kerr’s contribution and legacy. It dovetails with one her protégées, choreographer and dancer Faye Snow, who continued to promulgate Horton Technique in Philadelphia. Its intent is to whet interest, so that perhaps others will dig deeper and give a wider view, understanding and context of this legacy.

Interviews

Three interviews include Richard Moten, JKDC member, Paulette Poole who danced in JKDC and in Faye Snow’s Juba Contemporary Dance Theatre (JCDT) and Wayne David who danced in Juba. Each has a distinctive story to relate about what it was like to be a dancer during this time. They not only reference their experiences with Kerr or Snow, or both, but also tell how they each have become accomplished as teachers and choreographers in their own right as well. A fourth interview is with Randolph (Randy) Swartz, a dance presenter and businessman, who managed JKDC for a brief period near the end of her life. He produced the film, “A Dancer’s Class” choreographed by Kerr to demonstrate Horton technique studies. It is part of this collection.

In piecing together my own memory after my first encounter with Kerr at Temple University through Kathy Pira, I remember that I began to study Horton technique on a regular basis with Joan at her 3rd Street studio. It was a small converted storefront on south 3rd between Bainbridge and Fitzwater Streets, just off of South Street. At that time the neighborhood still had remnants of its Jewish immigrant history and longstanding Black community. I performed in school assembly programs, lec-dems, that Joan basically hustled school by school. I studied and worked with her for about two years before heading off to study at the Clark Center in New York City with Jimmy Truitte, (a Horton and Ailey company member). Then to broaden my experience in dance I attended the American Dance Festival when it was at Connecticut College in New London in ’68 and ’69. By then I was moving into the post-modern camp and was greatly interested in improvisation as performance. But to Kerr’s credit every dance technique class ended in free improvisation. It was my strength and enjoyment. Developing the essential dancer in this way, she had us improvise to an eclectic mix of music, compositions by local composer, Harold Boatwright to iconic Brahms waltzes.

Her personal life was one of unswerving bohemianism marked by social justice and love of all the arts. Her second husband Robert Summers was a playwright, who gave science lectures at the Wagner Free Institute for a living. Her small apartment on 6th Street was a hub for poets, writers, visual artists, musicians and dancers.

I also asked Gerry Givnish, co-founder and later Director of the Painted Bride Art Center about Joan Kerr. He said he met up with her when she was teaching at the Settlement Music School. She always had children’s classes and was an excellent teacher of young people. He said her children’s dance company performed at the Bride when it was a storefront gallery on South Street. She guided Gerry to other dancers/groups to perform there, including inviting me. She subsequently asked me to connect the Bride as a venue to other dancers. The Bride presented JKDC at the TLA (Theater of the Living Arts) on South Street ,after that theater company had folded and it had become primarily a repertory film house. He noted that she moved her studio to 13th & Race Streets around 1976. That was also the location of Swartz’s dance floor rental business, Stage Step. She and Bob Summers introduced Gerry to the poet Gerald Stern. The early Bride had poetry readings, music concerts and other events to draw in people to see the art on the walls by its painter founders, including Givnish, a visual artist.

Gerry’s comment to me was, “Please rescue those early days of the Philly art scene from oblivion!” Well, not sure I am capable of that – but I do share his palpable recall of the fervor of activity around that time.

In 1980 I reconnected with Joan at her invitation to be a guest artist in one of her works in homage to Horton dancer/teacher Joyce Trisler. I was honored to participate. Not long after that I saw Joan in the early Fall she had a wonderful summer tan from days spent on Long Beach Island at photographer, Harvey Finkle’s house. A little later she was diagnosed with a brain tumor. She died in January 1981. A memorial service was held in her Race Street Studio on one of the coldest days of that winter. Her young son spoke, and many people crowded in. I remember actress, Jane Moore comforting me. Painter, Sam Maitin and his wife Lilyan, and poet, Stephen Berg were there, as were many of her friends and dancers. A small handmade lacquered sign that hung in all her studios was still present. It was a quote from poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, “nor any altars in the sky except, fountains of imagination.” That pretty much summed up Joan Kerr’s influence on me.

Horton Technique is strong and vigorous and demanding. I like that about it. It seemed to me to bear little artifice in contrast to Graham technique. Kathy Pira was a polyglot of techniques and gave students a broad swath of a modern dance experience. She performed at Judson in NYC, and when she took sabbatical in 1966 she journeyed to Berlin to take classes with Mary Wigman in the last year of the Wigman Studio. Pira encountered a dance troupe with two Wigman students, Gruppe Motion Berlin, and persuaded three of the company members to emigrate to Philadelphia. Here they became know as Group Motion and Zero Moving, which made over the ensuing years an indelible impact on dance and dance education in Philadelphia.

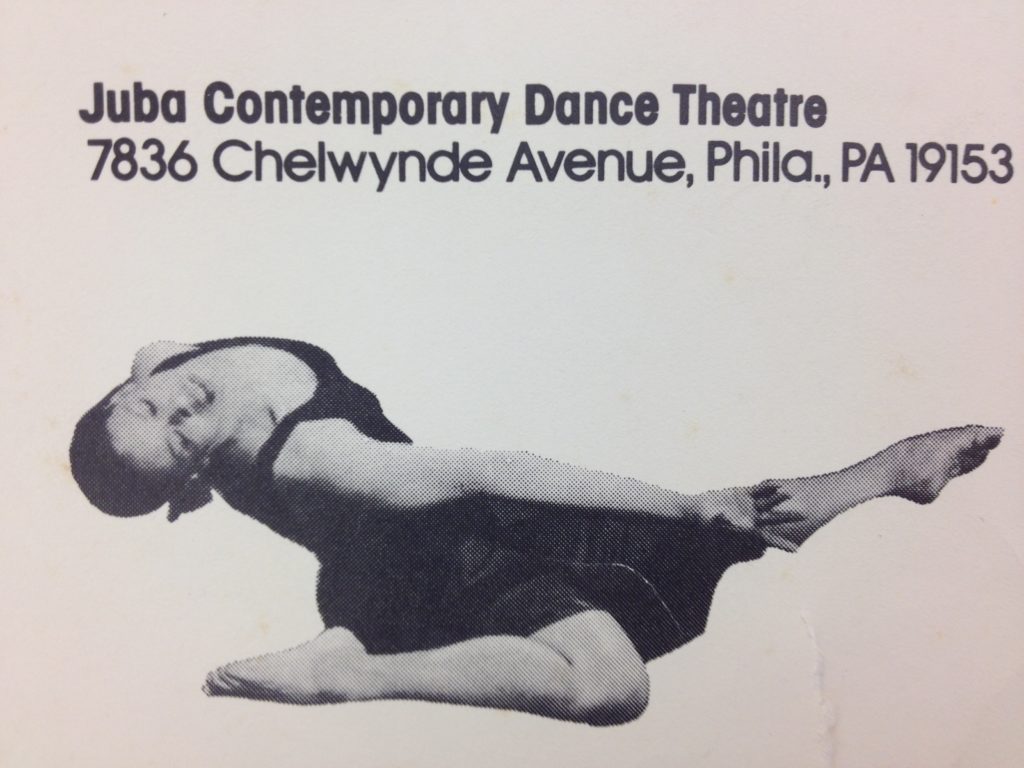

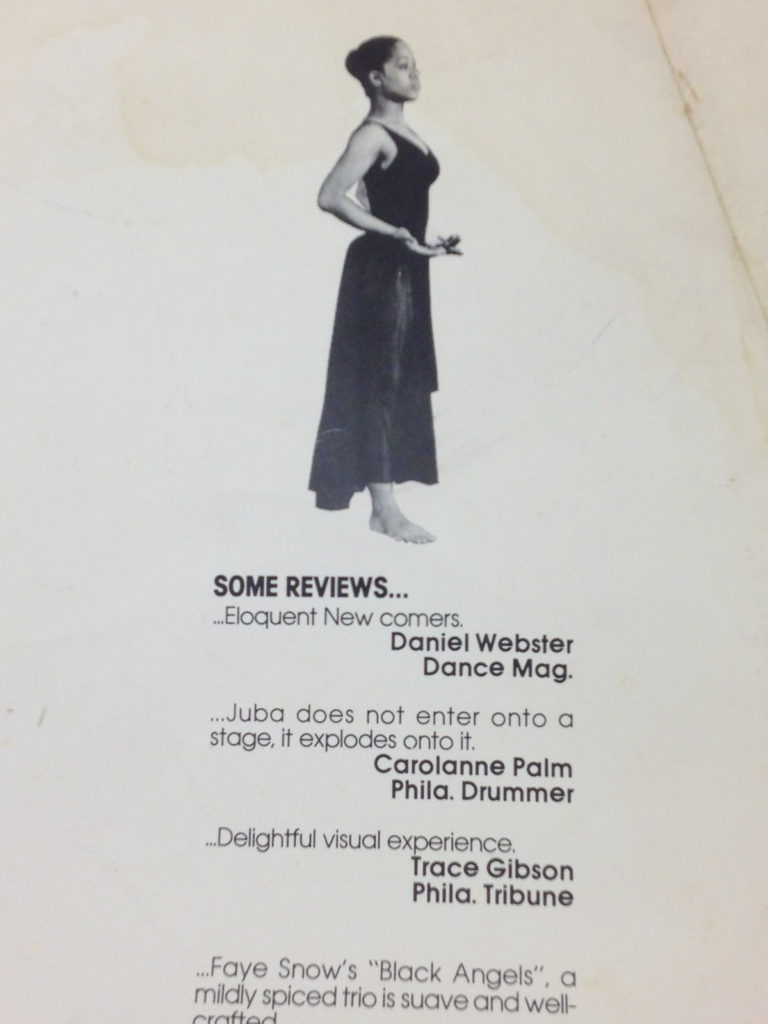

Faye Snow

Counter to the new Wigman presence in Philadelphia, Horton dance technique found its home primarily within a Black community of dancers. Perhaps since Alvin Ailey, a Horton company member had set the bar. Ailey’s American Dance Theater’s star Judith Jamison, was from Philadelphia and studied with Kerr as young dancer in the early ‘60’s. Dancer/Choreographer Faye Snow also studied with Kerr and she danced in her company. With an MA in Dance from GWU, Snow became a much sought after teacher of Horton technique at various schools and universities in the area. Her company Juba Contemporary Dance Theatre was founded 1973.

When I became “artist curator” at the Painted Bride, as it changed location and became an important center for showing and developing local artists along with their national peers, Juba Contemporary Dance Theatre was always included in the dance programming. Snow’s work represented a style with an emotional concern that carried on not only Horton choreodrama traditions, but infusions of themes and influences that were often inspired by Black culture and pop music.

NOTES ON INTERVIEWING:

These interviews are my first foray into collecting oral histories. A questionnaire was prepared with input from the Librarian and Director of the Special Collections Research Center at Temple University Libraries. All the interviewees saw the questions beforehand. All saw the raw transcripts. I did not realize that transcripts would not be kept in their raw format but rather would need to be edited for coherence and clarification. I have attempted to do that with all the interviewees’ input. In reviewing the transcripts I see in hindsight where I might have pursued a train of thought or questioning, but there was a learning curve in terms of staying in the moment and staying with the questions.

Some of the things that surfaced about the era in the interviews are very interesting to me. The sense of community divisions by race and by dance styles, seemed to be something touched on my all. Paulette Poole, Wayne David and Richard Moten are all dancers and choreographers and teachers and are African-American. I was a dancer, choreographer, teacher and curator/presenter. Randy was a dance presenter and businessman. We are Euro-American. Richard and Wayne both allude to the difficulty of being gay in the Black Community at that time.

For the dancers it was essential to find a way to survive economically. Richard, though he had a BA in Dance, held a job in civil service, was a hairdresser and choreographed for pop music stars. Wayne had a degree, too, and found opportunities to teach in higher education. Paulette held other jobs while teaching and performing. I did much of the same, having odd jobs and teaching until I returned to school to finish a BA degree. Randy’s presenting series Dance Celebration when it was at the Annenberg Center was heavily subsidized by the University of Pennsylvania, along with federal and foundation dance touring grants, while he had a thriving business selling dance floors and supplies to dance studios. His discussion about forming a dance service organization that was predicated on demonstrating knowledge of the community, showed how much it served his dance presenting directly, through member discount tickets to performances and members only access to master classes. He rarely presented or supported local companies in any substantive way. I feel this is an important contextual element in understanding this time period of dance in Philadelphia.

Local dance artists of all stripes had to forge their own way with little to no support by government agencies, private foundations, or large presenters of the kind that we are familiar with today. It is still a highly competitive environment and local dancers and companies still work hard to find the resources to keep them creatively solvent. Service organizations have come and gone. At present (2018) there is one online resource for information, listings and news, etc. and two local online journals for arts and dance coverage. There is sparse press coverage by the one daily paper. Weekly papers have all but disappeared. A supportive infrastructure in some ways resembles the era of Kerr and Snow. Artists can now use social networking for promotion, but that is limited in building a wider audience around a variety of styles and dance expressions.

All these personal takes on times past, all these conjuring of memories have value in trying to form a remembrance of Kerr and Snow as artists who employed Horton technique. The interviews demonstrate how shared and individual impressions can be. I hope some sense of the artists and their era surfaces with some degree of vividness and accuracy.

I wish to express sincere gratitude to Paulette, Richard, Wayne and Randy for the generous participation. Also thank you to Margery Sly, Director of the Special Collections Research Center for encouragement to gather more content for the Philadelphia Dance Collection at the Temple University Libraries.

Terry Fox

Local Dance History Project

Director, Philadelphia Dance Projects

05/28/2018